A journey through time, from the 4th century to the Monastery of Sant Cugat today

From the 5th century to the present day the place where the Monastery of Sant Cugat is located has been a strategic place in the history of Catalonia. We invite you to join us on this journey through time, from the Romans, through the Middle Ages and the Modern Age, to the contemporary era. You will learn about the historical events that marked the evolution of the Monastery of Sant Cugat and of Catalonia.

Octavianum – Roman background

The Monastery was established on a small hill in El Vallès plain, which is currently part of the historic centre of Sant Cugat del Vallès, very close to Barcelona.

In the low-empire era, sometime after 325, construction began on a fortification near Via Augusta. A castellum, with a square enclosure of 40 metres on each side, with walls and defence towers. There is a theory that Rufinus Octavianum, Comes of Hispania, promoted the work, thereby giving the place its name. Later the site began to have intense religious activity centred on a church built in the 5th century. This activity has been linked to the worship of the martyr Cugat, who according to tradition died in here, victim of the persecutions of Diocletian.

The domus of Sant Cugat, the foundation of the Monastery

It is not known when the Monastery was founded but we do know about the context. In the 9th century the Frankish monarchy promoted the creation of Benedictine monasteries as an instrument for organising its territories and transmitting the values of a new social order, feudalism. The choice of the old Roman settlement as the location of the new Monastery involved the survival or reuse of earlier buildings.

Counts and nobles, and especially owners of small and medium properties motivated by a pious spirit and the need to seek protection, made numerous donations. Thus, the properties of the monastic community began to grow from the mid-10th century and finally formed one of the most powerful ecclesiastical domains in the County of Barcelona.

Abbot Odó and the rise of the Monastery of Sant Cugat

When in 985 Al-Mansur laid siege to the County of Barcelona, some of the monks died and the Monastery was looted. One of the surviving monks, Odó, became the abbot and took on the task of rebuilding the Monastery. Odó obtained the nulla diocesis from Pope Silvestre II, a status that freed it from the bishopric and linked it directly to Rome. He also took charge of expanding the monastic properties and the construction of a new architectural site.

Monastic congregation centre

Sant Cugat played an important role in the development of Benedictine monasticism in Catalonia from the late 11th century. Its political influence as one of the largest monastic lordships and its proximity to the court of the County of Barcelona put it at the centre of many of the changes and reforms taking place in the ecclesiastical sphere. It benefitted from the political interests of the Counts of Barcelona and occupied a pre-eminent place within the Catalan Church.

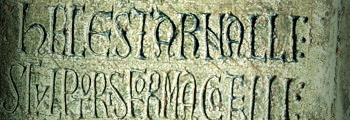

The Cloister of Master Arnau Cadell

The construction of a new monastery began from the mid-12th century. The monastery had notably increased its properties and the income generated enabled it to go beyond sustaining the monastic community and its function in the service of God. Thus, a new architectural project began in order to adapt the old buildings to the new needs of the community and the new times. The most characteristic development of that period was the construction of the Romanesque Cloister. Work on the Cloister began around 1190, designed by the master sculptor Arnau Cadell. It features a fabulous compendium of sculptures through its 144 capitals, an open door to the beliefs of the medieval world: they tell the story of salvation (south gallery) and show scenes of monastic life and motifs of symbolic value. Cadell left a self-portrait and personal inscription in the Cloister, which is unique and pioneering in the country and also denotes an important social status.

The relaxation of the Rule of Saint Benedict and the Monastery in the modern era

Throughout modern times, Sant Cugat maintained the prestige conferred as one of the largest ecclesiastical domains in the Principality, a rich monastery with a presence in the political and cultural life of the country.

In the process of setting up an absolute monarchy, control of the Church became one of the pillars of the royal policy, which directly affected the governance of monasteries. In the 16th century allegiance to Rome was replaced by submission to royalty, which retained the privilege of choosing the abbot until the last moment of the confiscation of ecclesiastical properties in 1835.

The Monastery and the conflicts in the modern era

The role of the Monastery and its abbots in two key episodes in the history of Catalonia, the Reapers War and the War of Spanish Succession, explains the links between the abbey and the political and social life of the Principality.

The specific case of the War of Spanish Succession (1702-1715) was a notable setback for the preeminent political power of the Monastery in the struggle between Philip V of Spain and Charles VI of Austria for the Hispanic throne. Abbot Baltasar de Muntaner supported Philip, while the Principality openly favoured Charles.Once the war was over, with the victory of Philip V, the new king ordered repressive measures against Sant Cugat, such as the demolition of part of the defensive elements – the machicolation and the entrance towers – to prevent any challenge from the abbey.

The end of the Monastery and its conversion into a monument

On 26 July 1835, the last monks of Sant Cugat left the Monastery forever bringing an end to a thousand years of monastic life. The extinction of the monasteries, however, began much earlier. The changes in mentality introduced by the Enlightenment in the 18th century cast the light of reason into the darkness of atavistic beliefs and questioned the established order. The structures of the Ancien Régime, such as the Church and monasticism, began to falter. With the 1835 confiscation of ecclesiastical properties, the monastic buildings lost their function. Thereafter, the future of the site was interwoven with the effort to preserve the monument and the opportunity to give it new uses at the service of the people.

In 1931 the Monastery was listed as a National Monument and the Government of Catalonia undertook new archaeological interventions in the Cloister, seeing the site’s potential for the first time with the discovery of the early Christian church. Currently, it is the property of the City Council, which has parish use of the church, perpetuating the Christian tradition in the Monastery, and cultural use of the monument, providing people with a place of enjoyment and learning.